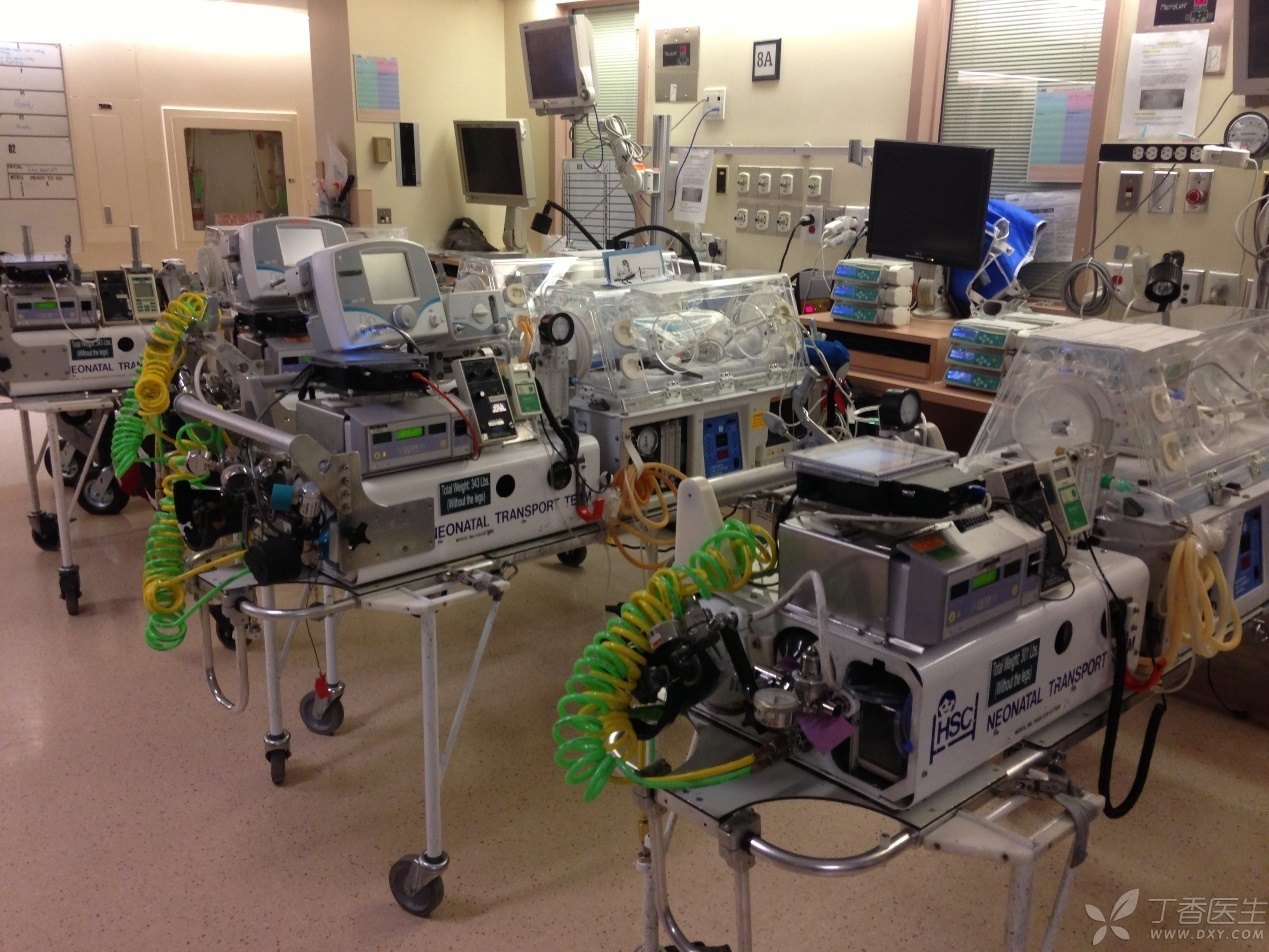

Five years ago, I just passed the examination in Toronto Children’s Hospital of the University of Toronto in Canada and became a specialist who was qualified to lead respiratory therapists or nurses to make visits for severe transportation. One thing happened, which had a far-reaching impact on my medical work and I still cannot forget it.

A rare severe case of newborn!

I was on duty that night, and just after midnight, the critical transfer hotline suddenly rang:

There is a shortness of breath baby 70 kilometers away who needs emergency assistance!

The illness was an order. My colleagues and I quickly tidied up the transfer warm box, rushed to the ambulance and pulled the siren to the destination.

On the way, the transfer coordinator of the rear base and I telephoned to communicate the child’s illness:

A full-term baby’s breathing gradually increases after birth. After comprehensive evaluation, the local secondary hospital provided the child with non-invasive ventilator-assisted ventilation support.

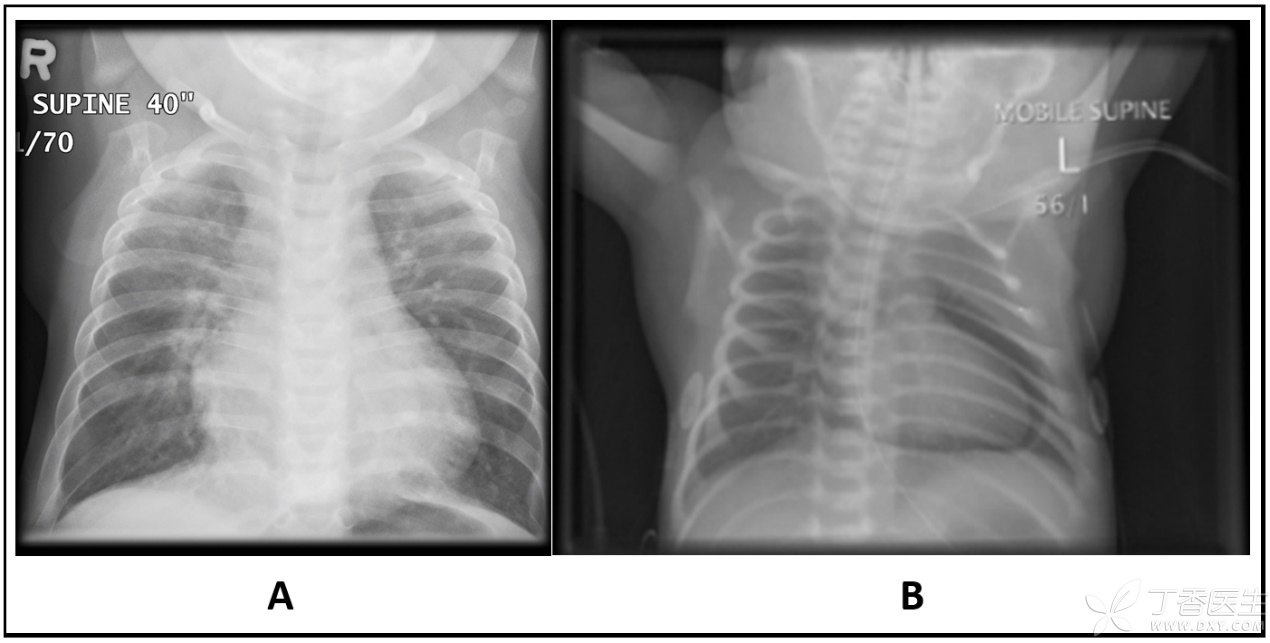

Tonight is the third day after giving birth, the child’s condition suddenly worsened and he began to have difficulty breathing. The chest radiograph for urgent examination did not see any obvious abnormality in the lungs, but accidentally found a large circle of gas around the heart and pericardial gas accumulation!

Friends with some medical knowledge should know, There is a layer of pericardium outside the heart, which is tightly wrapped around the heart like a heart coat. The gas between this coat and the heart is called pericardial gas, which is extremely rare in newborns. There is no pneumothorax or other forms of air leakage, and the pericardial gas in newborns alone is even less.

Looking back on the anatomy we have learned, we can certainly see that in the chest X-ray film on the right (B) below, there is a circle of air between the heart and pericardium. This circle of air wraps and presses the heart like an air cushion, limiting the beating of the heart to a certain extent.

If this restriction is serious (pericardial tamponade), it will directly lead to obvious abnormalities in the patient’s cardiac function, with very serious consequences.

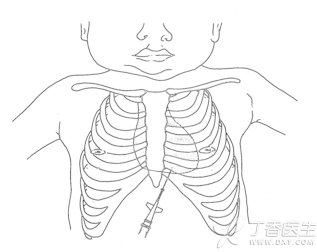

However, once pericardial tamponade occurs, our experience tells us that emergency pericardiocentesis is needed to decompress the heart.

Arrived at the hospital 70 kilometers away,

When I arrived at the hospital with my colleagues, I was first frightened by the unprecedented [welcome] appearance.

There were more than a dozen doctors sitting beside the child’s bed: pediatricians on duty that night and asking us for help, pediatricians in emergency department, adult emergency department doctors, otolaryngologists, general surgeons, anesthesiologists, etc.

The pediatrician on duty who called for help almost called the doctors who might do pericardiocentesis in the whole hospital that night to the ward to help. Unfortunately, she asked a circle, and no one had ever had the experience of pericardiocentesis in newborns and did not dare to start.

Pediatricians are worried, but fortunately the child’s heart function is still stable, and the pressure of the air cushion wrapping the heart on the heart is not obvious. The severe emergency team sent by the superior hospital is also approaching, so everyone simply sat by the bed waiting for me.

When I arrived with my colleagues, The patient’s condition was examined and evaluated according to the routine procedure. After synthesizing various indexes, I removed the non-invasive ventilator and immediately called the rear base to report my illness. As soon as the phone was connected, I asked the coordinator to call the director of the hospital’s cardiac specialty online, silently planning to tell him the current heart condition of the child in how’s way.

Soon, all the responsible doctors in the rear came to the line. I briefly summarized the situation of the child and began to focus on the current evaluation of cardiac function and the preparatory plan I had just drawn up for possible abnormal cardiac conditions.

No, the head of the cardiology department listened patiently to me and said calmly: [Just come back.]

I asked whether there was no need to prepare pericardiocentesis equipment in advance in case of changes in the disease during transit. The boss only replied with one word: [No.]

Cherish words like gold! I escorted the patient all the way back to the cardiac care unit of Toronto Children’s Hospital in fear and trembling. For nearly an hour, I kept the pericardiocentesis equipment within easy reach.

He nervously transferred the child back to the base and finally handed over the patient.

The director on the phone brought the resident on duty. The resident and I started to actively prepare all kinds of rescue equipment, and then asked the director, we are now doing what treatment. The director said softly: [Do nothing.]

The lower-level doctor asked with a face of incomprehension, if he did nothing, why did he transfer the patient?

The director smiled and said something that I will never forget: [Sometime it takes lots of knowledge and experience to do nothing] (sometimes what does not do it in the face of patients, in fact, doctors need to have solid basic skills and rich experience).

Let go of… … …

Looking at the unprepared cardiac resident around me, I also smiled. Only then did I react that the cardiac expert had already made a judgment on the patient’s condition and the development of his illness.

He decided from the very beginning: No intervention is the best choice. He has seen through the development of the whole course of the disease and the possible situation. After making many analyses in his heart, he told everyone not to do it in what. The expert seemed that what didn’t do it, but in fact he did it in his heart in what. He handled the situation that made others so nervous and helpless, but the wind was light and the clouds were light.

When a doctor is facing a patient’s discomfort, he sometimes advises the patient to observe for the time being instead of doing what. Most doctors who give such advice have already thought a lot about the possible situation in their hearts and weighed the relevant further evaluation or treatment methods.

The more such advice is given to a doctor, the higher his standard is. Unless he does not understand what, he is likely to know a lot. Dear, Sometime it takes lots of knowledge and experience to do nothing!

Why didn’t what do it?

After filling chicken soup, talk to interested colleagues briefly about why the child does not need urgent pericardiocentesis. Temporary dyspnea (also called wet lung) is one of the most common respiratory problems in full-term newborns.

When the fetus is in the mother’s belly, the alveoli of both lungs are amniotic fluid. Wet lungs will occur if more liquid remains in the alveoli after birth and affects gas exchange. Wet lungs of newborns, mostly mild, gradually recover within a few days with the absorption of liquid in the lungs.

Because newborns’ wet lungs are often self-limited, it is more appropriate to closely monitor the changes of the disease condition than to actively intervene at an early stage.

In some cases, doctors do not have a reasonable grasp of the indications for the use of non-invasive assisted ventilator. It is possible to give full-term newborns with wet lungs continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) through the nose early on. Such ventilation is very uncomfortable for full-term older children. As a result, many babies are very agitated, and their spontaneous breathing and body movements are constantly resisting the ventilator. If this situation is not controlled, it will often lead to severe pulmonary hypertension or air leakage (pneumothorax, mediastinal pneumatosis, pericardial pneumatosis, etc.).

In addition, if the neonatal respiratory condition has obviously improved under the support of non-invasive assisted ventilation, and the ventilator parameters have not been adjusted accordingly, higher pressure will continue to impact the neonatal lungs and will easily lead to air leakage.

Before the so-called disease change occurred on the third night, all respiratory indexes of the child were improving, and the support level of the non-invasive ventilator remained at a relatively high level, so higher pressure may be the main cause of the air leakage.

Interestingly, pneumothorax is the most common occurrence of air leakage in most children, and this baby is a simple pericardial gas accumulation, so bilateral lungs are not greatly affected.

After I got the detailed information from the local hospital, I went back to analyze the [dyspnea] that night. In fact, the evidence was not sufficient. It was not ruled out that it was only a period of incompatibility between the child and the ventilator. This can better explain why the overall condition of the child improved after the ventilator was removed.

The doctor on duty in the second-class hospital that night, because he saw pericardial gas accumulation on the chest radiograph, was full of thoughts on how to deal with it and who to find to do the puncture. He was very worried about the possible pericardial tamponade. Because of this relatively rare situation, her clinical thinking was disrupted. Whether respiratory support is necessary or not, there is a lack of careful thinking.

My own reflection from this point is that when I encounter rare situations in clinical practice and do not know that how is a good treatment, I should first return to the most basic A (cleaning respiratory tract), B (breathing) and C (circulation) step by step analysis.

The more complicated the situation is, the more calm is needed. Removing or controlling the cause of the disease should be the top priority in the treatment strategy.

After my colleagues and I removed the child’s non-invasive assisted breathing, the child’s breathing condition did not deteriorate. On the contrary, the child was extremely comfortable with a small dose of sedatives because of the lack of this very uncomfortable nasal obstruction that has been jet.

After removing the cause of pericardial pneumatosis, the possibility of aggravation of pericardial pneumatosis becomes very small. Without continuous asphyxia resuscitation or positive pressure ventilation, most pericardial pneumatosis does not require active intervention, which is the main reason why the director of cardiology thinks pericardiocentesis is not needed.

Of course, there are some other support points, which will not be listed one by one. We also made some corresponding adjustments to many drugs and sedation management that night.

Finally

The child finally stayed in the cardiac intensive care unit of Toronto Children’s Hospital for two days and was transferred to the general ward. About a week later, the child went through the discharge formalities. I looked at the chest radiograph of the pre-discharge review on PACS imaging system and found that pericardial pneumatosis had completely disappeared.

Finally, I would like to share with all the young doctors who are advancing on the medical road:

When you encounter interesting clinical cases or problems with a senior doctor, even if TA is the same as your strategy, ask one more reason.

A master plays chess. Maybe he takes the same step as you think when watching after thinking about countless changes and moves. You smile and think you understand, but in fact you may never understand the changes behind it.

For example, I also found the opportunity to talk face to face with the director of cardiology in this case. Although I had some of his thoughts, the director still had many other thoughts that benefited me greatly.