No matter the doctor of what Department, he is familiar with hypertension.

However, hypertension must be reduced to what’s level before it is considered [best]? This is difficult for even many cardiologists to answer correctly. Is there a lower limit for lowering blood pressure? Is the lower the blood pressure, the better the protection of organs? Or is it enough to maintain a reasonable level?

For a long time, the determination of the best pressure control target for hypertension patients has been controversial, especially for hypertension patients complicated with coronary artery diseases.

Strict pressure control is written into the guide.

In April this year, the Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) Committee of Experts released an update of the 2016 Hypertension Guidelines, formally adopting the SPRINT study’s [intensive antihypertensive] strategy:

The blood pressure target value of high-risk patients (with cardiovascular diseases, 10-year cardiovascular risk > 15%, or older than 75 years old, etc.) should be below 120 mmHg.

The theory of “strict pressure control”, that is, “the lower the blood pressure, the better”. This theory began in the TOMHS study in 1991 [4].

The stronger study was the SPRINT trial published by NEJM in 2015. This is a large randomized controlled clinical study organized by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). A total of 9,361 subjects were included and randomly assigned to the enhanced hypotension group (systolic blood pressure less than 120 mmHg) and the standard hypotension group (systolic blood pressure less than 140 mmHg).

The results showed that intensive hypotension with systolic blood pressure less than 120 mmHg could reduce the risk of death and cardiovascular events by 30% and 25%, respectively.

In 2014, the U.S. Hypertension Guidelines (JNC8) recommended on the basis of JNC7 that the general population aged ≥ 60 years old should reduce their blood pressure to the target values of systolic blood pressure < 150 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg. SPRINT poses a great challenge to this relaxed antihypertensive strategy.

In our country, although the target of lowering blood pressure is still 140/90 mmHg (130/80 mmHg for people with basic diseases and 150/90 mmHg for the elderly) in the current hypertension guidelines, research has been carried out on whether lowering blood pressure to 120 mmHg will benefit.

However, has the dust settled?

However, Lancet recently said something

As early as 1979, Stewart [3] found in a retrospective statistical study that the relative risk of myocardial infarction in patients with diastolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg was 5 times higher than that in patients with diastolic blood pressure greater than 100 ~ 109 mmHg. This is the first time to put forward the [J-curve] theory:

The decrease of blood pressure, especially diastolic blood pressure, will increase the risk of cardiovascular complications.

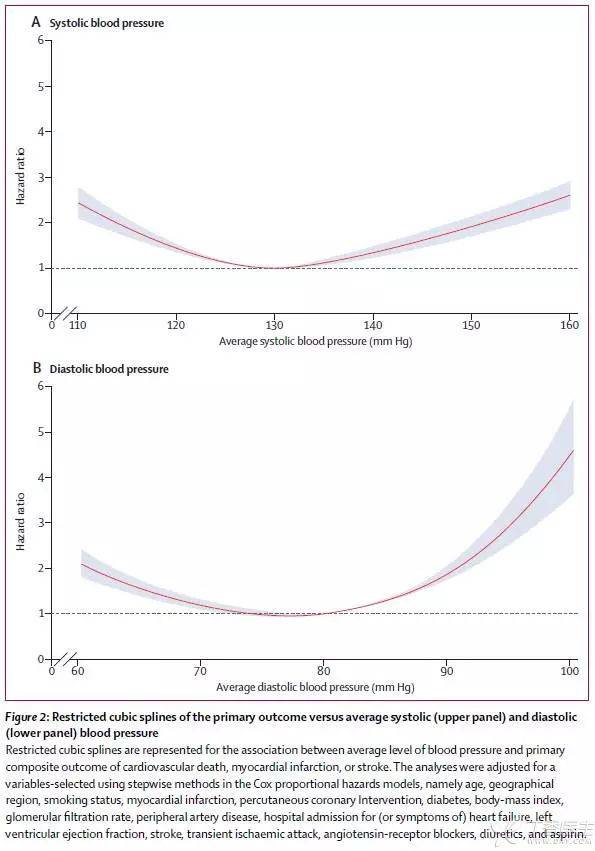

On August 30 this year, Lancet published a study online by Professor Emmanuelle Vidal-Petiot from the Institute of Cardiovascular Disease of Diderot University in Paris [1], which included 22,672 hypertension patients from 45 countries with stable coronary artery disease.

Its research shows that in patients with hypertension complicated with coronary artery disease, controlling blood pressure to systolic pressure < 120 mmHg and diastolic pressure < 70 mmHg are all related to the occurrence of cardiovascular adverse events (cardiovascular disease death, myocardial infarction or stroke).

The study found that systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mmHg are both associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events, which is consistent with previous studies.

However, systolic blood pressure < 120 mmHg is also associated with the risk of cardiovascular events. In addition, diastolic blood pressure < 70 mmHg is also associated with an increase in the main study outcome, and if diastolic blood pressure < 60 mmHg, there will be a greater risk.

Professor Giuseppe Manciae (University of Bicoca, Milan, Italy) wrote in his commentary [2]:

Strict control of blood pressure below 120/70 mmHg can significantly increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction and heart failure, which suggests that we should take a cautious attitude in antihypertensive treatment of patients with coronary artery diseases.

Who is right to strengthen depressurization and J-curve?

As we all know, the [Daniel] research published every year in [Daniel] journals such as NEJM, JAMA and Lancet is a barometer of changes in major guidelines and plays an important role in the process of formulating guidelines.

Therefore, when there are such great differences in the studies of these magazines in the same period, it also shows that it is difficult to reach a consensus on this point clinically.

However, after analyzing the results of various subgroups in SPRINT test, some careful scholars found that, The benefits of stricter blood pressure control mainly lie in the subgroup of baseline blood pressure ≤ 132 mmHg, which does not belong to hypertension population according to current standards, while in prehypertension and hypertension population (baseline systolic blood pressure > 132 mmHg), stricter blood pressure control has not significantly benefited [6].

Lancet’s study undoubtedly won a victory for the party supporting the [J-curve] for the time being. We do not know whether it can push for further changes in the guidelines, but the controversy over the [best blood pressure target] will definitely not stop because of this.

Is the blood pressure of hypertension patients controlled below 120 mmHg an additional benefit or an additional risk? What criteria should we adopt in clinical practice? China’s guidelines have to wait for the results of China’s own test data.